Kursk Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 1

Kursk

Russia

Pre-Trial Detention Centre

Active

Overview

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kursk Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 1 was one of the primary detention facilities for Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians, both men and women. Prisoners were brought here from various locations, sometimes for just one day, others for several months.

The detention centre consists of a complex of buildings – one old structure and three new ones with an official capacity to hold more than 900 prisoners. According to testimonies, cells often held 12 to 22 prisoners. One prisoner recalled a cell measuring 2.5 meters in width and 6 meters in length, where 12 men were kept in a space designed for six.

A female detainee described being held in a six-person cell with 11 women. Despite the overcrowding, she noted that compared to previous facilities, conditions here were somewhat better: the toilet was separated from the main room, the windows, though covered with plastic film that blocked visibility, could be opened independently.

Torture & Abuse

POWs describe the “admission” procedure as the worst part of every Russian prison. Upon arrival at Kursk, prisoners were subjected to beatings. One former POW was brought in at 11:00 a.m., and by 3:00 p.m., an ambulance had to take him to intensive care after being brutally beaten, including a deliberate blow to his recently operated arm that re-fractured the bone.

Beatings during admissions were systematic. Prisoners were hit with batons, shocked with tasers, and humiliated. Guards intensified abuse following Russian military losses on the battlefield, taking out their anger on the detainees. Interrogations also often involved torture.

Medical Care

Medical care in Kursk was minimal and often delayed. Seriously wounded prisoners did not receive immediate attention. One Ukrainian soldier recounted that after being brought to the detention centre at the end of April 2022, his first bandage change was carried out only on the fifth day.

Subsequent care was superficial: bandages were removed, but the wounds were not cleaned or disinfected. No proper medical inspection followed – instead, guards re-wrapped the injuries. This often led to infections.

Another prisoner, who had previously undergone surgery for a severe injury to his left arm, was beaten during admission, including a direct strike to the operated area. This attack caused the arm to break again.

Eventually, some prisoners with more serious conditions were transferred to a local hospital, but only after significant delays.

Food & Sanitation

Prisoners reported that guards often ate the food meant for them. Meals frequently consisted of diluted porridge, cabbage soup, or waterlogged mashed potatoes. When available, half a loaf of bread per person was the main source of nutrition.

Prisoners were allowed to shower only three times per month, with five minutes per person and no hygiene products, including for women. Soap and toilet paper were virtually unavailable. Asking for anything often resulted in beatings.

Psychological Pressure

The day began at 6 a.m. with the Russian anthem, which prisoners were required to sing. They were given printed propaganda songs and poems about Russia to memorise.

Guards forced prisoners to memorise and recite information about Russian symbols and history. Books with pro-Russian themes were read aloud, and prisoners were not allowed to sit on beds during the day – only on benches or the floor.

Evening searches were routine. Once a week, a more invasive inspection was conducted, involving complete cell sweeps and occasional beatings. Outside walks were rare and often turned into beatings.

Testimonies & Reports

“The worst part of every detention centre is the admission. I was brought to Kursk at 11 a.m., and by 3 p.m., an ambulance had to take me to intensive care” – prisoner of war.

“Our cell was 2.5 meters wide and 6 meters long. There were 12 of us, even though the cell was designed for six. They welded extra beds so that everyone had a place to sleep. The cell was very damp, and the conditions were poor” – prisoners of war.

“They ate all our food themselves. We could hear the guards sitting outside our cell, smacking their lips, even eating the barley porridge. Then they would dilute the leftovers with cold water. Sometimes I had just 2–3 spoonfuls of porridge in my bowl, the rest was water. They’d give us cabbage broth and the same cabbage, maybe four spoonfuls if we were lucky. Dinner was potatoes and fish, but calling it ‘potatoes’ would be generous – it was mostly water, with a few chunks if we were lucky. Once the fish ran out, they started giving us canned fish. It looked like regular sardines in oil, but when half a can is split between eight people, you don’t get much to eat” – prisoners of war.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kursk Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 1 was one of the primary detention facilities for Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians, both men and women. Prisoners were brought here from various locations, sometimes for just one day, others for several months.

The detention centre consists of a complex of buildings – one old structure and three new ones with an official capacity to hold more than 900 prisoners. According to testimonies, cells often held 12 to 22 prisoners. One prisoner recalled a cell measuring 2.5 meters in width and 6 meters in length, where 12 men were kept in a space designed for six.

A female detainee described being held in a six-person cell with 11 women. Despite the overcrowding, she noted that compared to previous facilities, conditions here were somewhat better: the toilet was separated from the main room, the windows, though covered with plastic film that blocked visibility, could be opened independently.

POWs describe the “admission” procedure as the worst part of every Russian prison. Upon arrival at Kursk, prisoners were subjected to beatings. One former POW was brought in at 11:00 a.m., and by 3:00 p.m., an ambulance had to take him to intensive care after being brutally beaten, including a deliberate blow to his recently operated arm that re-fractured the bone.

Beatings during admissions were systematic. Prisoners were hit with batons, shocked with tasers, and humiliated. Guards intensified abuse following Russian military losses on the battlefield, taking out their anger on the detainees. Interrogations also often involved torture.

Medical care in Kursk was minimal and often delayed. Seriously wounded prisoners did not receive immediate attention. One Ukrainian soldier recounted that after being brought to the detention centre at the end of April 2022, his first bandage change was carried out only on the fifth day.

Subsequent care was superficial: bandages were removed, but the wounds were not cleaned or disinfected. No proper medical inspection followed – instead, guards re-wrapped the injuries. This often led to infections.

Another prisoner, who had previously undergone surgery for a severe injury to his left arm, was beaten during admission, including a direct strike to the operated area. This attack caused the arm to break again.

Eventually, some prisoners with more serious conditions were transferred to a local hospital, but only after significant delays.

Prisoners reported that guards often ate the food meant for them. Meals frequently consisted of diluted porridge, cabbage soup, or waterlogged mashed potatoes. When available, half a loaf of bread per person was the main source of nutrition.

Prisoners were allowed to shower only three times per month, with five minutes per person and no hygiene products, including for women. Soap and toilet paper were virtually unavailable. Asking for anything often resulted in beatings.

The day began at 6 a.m. with the Russian anthem, which prisoners were required to sing. They were given printed propaganda songs and poems about Russia to memorise.

Guards forced prisoners to memorise and recite information about Russian symbols and history. Books with pro-Russian themes were read aloud, and prisoners were not allowed to sit on beds during the day – only on benches or the floor.

Evening searches were routine. Once a week, a more invasive inspection was conducted, involving complete cell sweeps and occasional beatings. Outside walks were rare and often turned into beatings.

“The worst part of every detention centre is the admission. I was brought to Kursk at 11 a.m., and by 3 p.m., an ambulance had to take me to intensive care” – prisoner of war.

“Our cell was 2.5 meters wide and 6 meters long. There were 12 of us, even though the cell was designed for six. They welded extra beds so that everyone had a place to sleep. The cell was very damp, and the conditions were poor” – prisoners of war.

“They ate all our food themselves. We could hear the guards sitting outside our cell, smacking their lips, even eating the barley porridge. Then they would dilute the leftovers with cold water. Sometimes I had just 2–3 spoonfuls of porridge in my bowl, the rest was water. They’d give us cabbage broth and the same cabbage, maybe four spoonfuls if we were lucky. Dinner was potatoes and fish, but calling it ‘potatoes’ would be generous – it was mostly water, with a few chunks if we were lucky. Once the fish ran out, they started giving us canned fish. It looked like regular sardines in oil, but when half a can is split between eight people, you don’t get much to eat” – prisoners of war.

News

see more

“The captives were forced to walk with their heads down”: how the rehabilitation of released Ukrainian soldiers takes place

Ukrainian servicemen released from Russian captivity often arrive at the National Guard’s medical centre in extremely poor condition, both physically and psychologically.

Russia has established a network of torture chambers for Ukrainian prisoners of war.

At least five secret prisons in Russia are holding Ukrainian POWs.

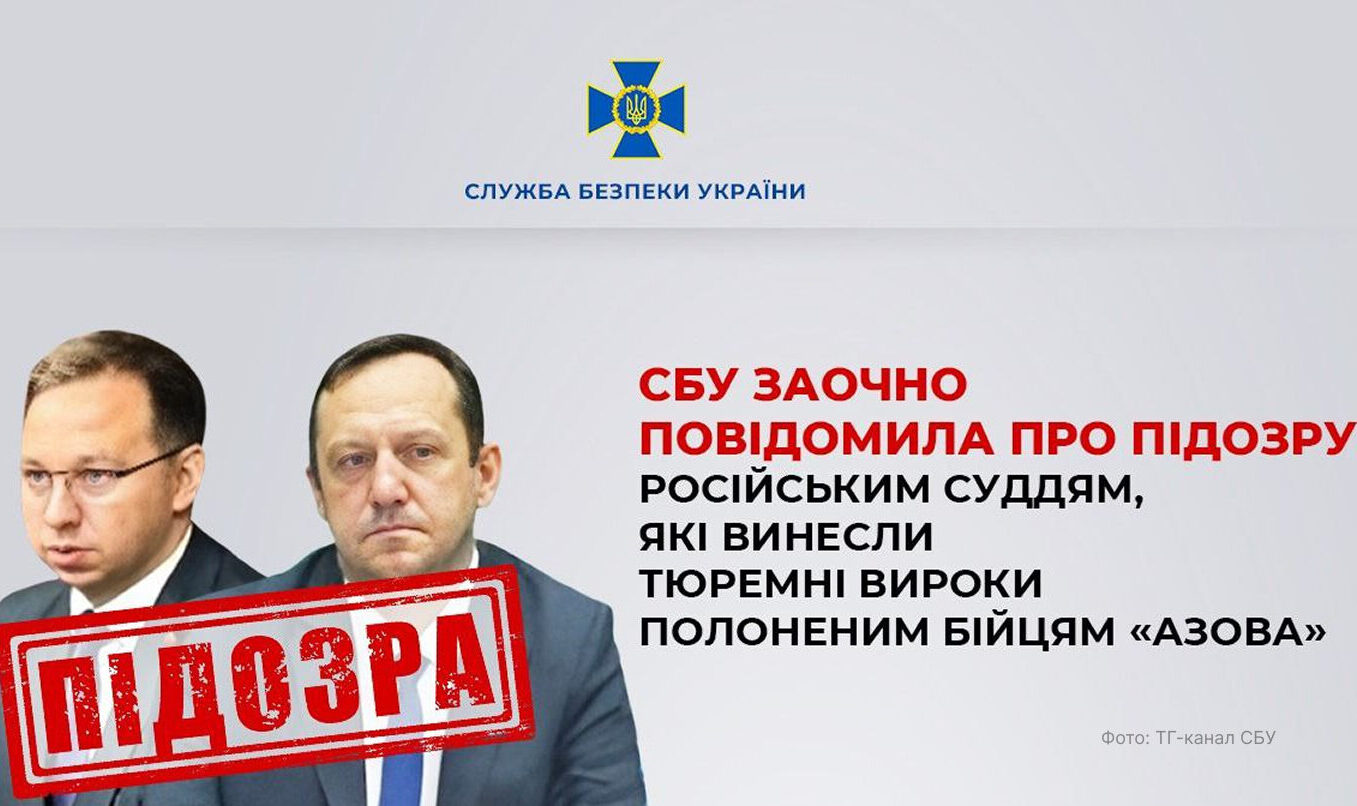

SBU presses charges against russian judges for the unlawful sentencing of Azov Brigade POWs

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) has charged in absentia two judges of Russia’s Southern District Military Court, Konstantin Prostov and Sergey Obraztsov, with war crimes against Ukrainian prisoners of war.

questions & answers

You can make a difference

Have a question, a message, or something important to share?

Whether it’s information, a concern, or a word of support, we want to hear from you.

Every voice matters.