Volnovakha Penal Colony No. 120, Olenivka

Donetsk Oblast, Volnovakha District, Olenivka

Temporarily occupied territories

Penal Colony

Unknown

Overview

Volnovakha Penal Colony No. 120, located near the village of Olenivka in the Russian-occupied part of Donetsk region, was originally a disused Soviet-era correctional facility. Prior to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, it was decommissioned and uninhabited. After the invasion began, Russian forces reactivated the site and repurposed it into an improvised detention facility for Ukrainian prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians.

From March 2022 onward, Olenivka colony became one of the central locations where Ukrainian POWs captured in Mariupol were held, including members of the Azov Regiment, the 36th Marine Brigade, border guards, and National Police officers. In addition, Ukrainian civilians, including volunteers and evacuees, were detained and held in horrific conditions despite their protected status under international law.

The colony’s proximity to the front line (approximately 14 km as of July 2022) placed detainees at constant risk, a direct violation of international humanitarian law, which requires POWs to be held in safe locations away from active hostilities.

The Olenivka War Crime

Mass execution in Olenivka in the early hours of 29 July 2022, stands out as one of the gravest war crimes against POWs when at least 53 Ukrainian POWs were murdered, with another nearly 139 injured. Those killed or wounded were members of the Azov Brigade who had surrendered from the Azovstal steel plant.

Two days before the incident, 193 Azov servicemen were moved into the industrial barrack. On the evening of 28 July, the POWs were locked inside the barracks, and just a few hours later, explosions occurred. Following the explosions, prison guards and leadership refused to help the wounded. Instead, they were seen standing and sipping coffee at the site of the massacre or firing into the air to prevent survivors from approaching the gates. Immediately after the explosion, colony staff freely moved around the colony without fear of subsequent shelling, despite later claims by Russia that the explosion was due to Ukrainian shelling. Despite the arrival of ambulances, the colony staff deliberately refused to provide medical aid to the injured POWs.

Following the mass killing, surviving POWs, including many severely injured, were forced to clean up the site, remove corpses and debris, and sort through body parts in the ruined barrack, according to OHCHR findings.

The ICRC was unable to gain access to the Olenivka Colony after the mass killing. Furthermore, the UN’s response to the Olenivka war crime was weak. Although Secretary-General Guterres launched a Fact-Finding Mission in August 2022, it never visited Ukraine and was disbanded in January 2023. Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets criticised the mission’s composition, which included biased individuals, such as Brazilian General Carlos dos Santos Cruz, a former military attaché in Moscow and Minister-Secretary in the government of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. A few days before the war began, on February 16, 2022, Bolsonaro met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, where he expressed “solidarity” with Russia.

Another member of the Mission was Ingibjörg Gísladóttir, who had been repeatedly criticised for ignoring Russian human rights violations while at the OSCE. The decision to shut down the Mission without results underscored the UN’s inability to act effectively in the face of Russian aggression.

In December 2024, Human rights organisations filed a submission with the International Criminal Court calling for an investigation into the mass murder and torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war in Olenivka.

Torture & Abuse

According to numerous testimonies from former detainees and reports by international organisations, systematic torture, physical violence, and horrific treatment were widespread at Penal Colony No. 120 in Olenivka. These practices were a routine part of the facility’s function under Russian control.

Detainees were frequently blindfolded with duct tape, their hands bound, and hoods placed over their heads during transport or movement. Any perceived disobedience, including sitting or lowering one’s hands incorrectly, could result in beatings with rubber batons. Detainees, including both civilians and former soldiers, were tortured with electric shocks. Electrodes were attached to their toes or their bodies were sprayed with water before being shocked while lying on metal tables.

The so-called “disciplinary isolation block” (DIZO) was one of the most brutal episodes described. There, women and men were held in overcrowded, unsanitary cells with no access to functioning toilets, often forced to defecate where they slept.

The colony’s overcrowding itself became a method of torment. According to testimonies, up to 20 people were put in cells designed for 4 and 55 POWs were put in cells designed for 8. Prisoners had to sleep in shifts on concrete floors, deprived of bedding and fresh air. Screams of beaten POWs were heard every night from nearby cells.

Medical Care

Medical care in Olenivka Penal Colony No. 120 was nonexistent and deliberately denied. Multiple testimonies from former detainees describe medical neglect, lack of access to essential care, and cruel disregard for suffering.

Wounded Azovstal defenders received only minimal painkillers upon arrival. Many were left without proper treatment for severe injuries, including shrapnel wounds, broken limbs, and internal bleeding. There were no medications, no doctors, and no boiling water available for the sick.

After the Olenivka war crime in July 2022, dozens of severely injured POWs had to wait for hours before being evacuated, but not by ambulance, but in KAMAZ trucks. With gunshot wounds, burns, and internal trauma, they were thrown into the metal beds of trucks, forced to crouch or lean on their hands to avoid the searing pain from sitting on the hard floor. Some of the wounded never made it to surgery in time. Medical assistance was often provided only because the explosion had caused public visibility, briefly interrupting the usual neglect.

The OHCHR noted that following the mass killing, injured POWs were given no professional medical aid inside the colony. Instead, other detainees cared for them, using rags and bare hands. Some of the wounded bled out, waiting for help.

Food & Sanitation

Starvation, thirst, exposure to human waste, and denial of hygiene were widespread tools of repression. Basic survival needs were used as levers of coercion and submission. Daily food rations were meagre and given in dirty dishes. Clean drinking water was a luxury. Detainees received no more than 150–200 ml of drinking water per day, and even that was not guaranteed. Technical water, used for washing and sanitation, was also rationed and often unavailable for several days at a time. Guards explicitly told POWs: “Be grateful we feed you at all”.

Toilets in the disciplinary isolation unit were non-functional. Waste accumulated in clogged drainage pits, releasing stench and serving as a source of disease. For the first weeks, the use of the toilet was forbidden, which was another method of deliberate humiliation and torture. Prisoners had to relieve themselves in buckets or not at all.

Women in detention were denied basic hygiene products, including menstrual pads, for months. Without access to any sanitary materials, women were forced to bleed in clothing and sleep on blood-stained concrete floors. There were women of all kinds – pregnant, mothers of small children, National Guard accountants, and completely civilian women.

Psychological Pressure

Captivity in Olenivka Penal Colony No. 120 was built around a system of total control, fear, and mental exhaustion. Prisoners were subjected to conditions designed not only to break their bodies, but also to crush their will and identity.

Detainees were deprived of any connection to the outside world and held in total informational isolation. Instead, they were exposed only to Russian propaganda and false reports. POWs were told that Kharkiv was already occupied and Russian forces were already near Kyiv.

Sensory deprivation and constant uncertainty were key methods of pressure. Prisoners were regularly blindfolded, had their hands and eyes taped, or were forced to keep their heads down for hours at a time during transfers and interrogations. Lights in cells were left on around the clock, or, conversely, cells were kept in total darkness. Loud noises, shelling, shouting, or the cries of tortured detainees were a constant background sound.

Detainees were told they would be held in the colony “for 10 years or more,” or, as prison chief Serhiy Yevsyukov often put it, that their families would be told they had “flown into space”.

Interrogators and guards often played psychological games, threatening collective punishment or promising exchanges that never came. At times, guards forced prisoners to step over a Ukrainian flag, and those who refused were punished.

Testimonies & Reports

A truck stopped near the barracks, releasing two or three people at a time. About ten soldiers in balaclavas stood nearby with dogs and batons. They began beating our boys. We watched from the windows of our buses. Then they were ordered to run. As they did, the dogs were unleashed and bit at their legs. When the boys fell, they were beaten again with batons. It happened to every one of them” – Anastasiia Rustamova, 36th Separate Naval Infantry Brigade, on the “reception” at Olenivka Colony.

“His call sign was ‘Casper.’ A quiet, calm guy. He was ‘300’ [wounded] — he’d survived two airstrikes in Mariupol and suffered facial burns. During the ‘reception,’ he was beaten to death… He stood right in front of me. If he hadn’t died, they would have beaten us, those of us standing behind him, with the same force… There was a guy on a crutch. They took his crutch and beat him with it. I saw him lying while the prison guards stood over him, just watching to see what would happen next” – а combat medic on the “reception” at Olenivka Colony.

“A half-destroyed building with shit dripping down the walls, perpetually clogged sewage, and freezing cold. It was always cold, all the time. Mostly because of the concrete floor. No benches, no beds, nothing to lie on properly. The toilet was right inside the cell, always blocked and unusable. The walls were covered in mould and fungus. Cold and concrete… We constantly heard the beating of prisoners of war. At the same time, they played music to drown out the screams of pain” – Kostiantyn Velychko, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“An Azov fighter was beaten upon arrival — so badly he couldn’t rise from his knees. One of the guards shouted, ‘Look, they brought fresh meat!’ Then they forced him to clean the toilet with his bare hands” – а prisoner of war on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The guys told us they had been physically abused. The Russians attached electrodes to their toes or placed them on a metal table, sprayed them with water, and turned on the power” – Kostiantyn Velychko, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The sewage system was set up in such a way that everything simply accumulated in a drainage pit, which was always clogged. During the first weeks, it was especially unbearable — they didn’t allow us to use the toilet. That was a specific form of torture. We were surrounded by filth, decay, and freezing cold” – Hanna Vorosheva, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“Drinking water was something we especially lacked. We could expect just 150–200 ml per person per day. Sometimes, we didn’t even get that” – Hanna Vorosheva, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The administration representatives calmly watched people die through the night. All they were missing was popcorn. Through the fence, they watched me perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. They didn’t arrange any evacuation. During that time, five more people died — people we couldn’t help… Everyone was transported in ordinary trucks” – а combat medic on the explosion in the barracks.

“In addition to shrapnel, our bodies were full of mineral wool fibres. For a month afterwards, we kept pulling those needles out. It burned. Can you imagine mineral wool burning? Your whole body itches and burns. And we were barefoot — our feet shredded from walking over broken glass and debris. Many of our guys suffered severe burns” – Azov serviceman, call sign “Lemko,” on the explosion in the barracks.

“I know there were ambulances behind the gates. We heard them. They arrived 30 minutes after the explosion. We even passed them one of our wounded, call sign ‘Karas.’ We passed him under the fence in a sleeping bag. After some time, they returned him. He was still alive. They said he had no chance. We asked, ‘Should we hand over someone else?’ They said no. Then we asked for a needle so we could perform a decompression on those with chest wounds. They refused” – Azov servicemen on the explosion in the barracks.

“Nothing can prepare you for what we saw there. The entire walkway was covered in blood. People were just crawling — something I could never have imagined. Some had traumatic amputations, deep abdominal wounds, head injuries, or multiple shrapnel wounds” – а combat medic on the explosion in the barracks.

Volnovakha Penal Colony No. 120, located near the village of Olenivka in the Russian-occupied part of Donetsk region, was originally a disused Soviet-era correctional facility. Prior to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, it was decommissioned and uninhabited. After the invasion began, Russian forces reactivated the site and repurposed it into an improvised detention facility for Ukrainian prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians.

From March 2022 onward, Olenivka colony became one of the central locations where Ukrainian POWs captured in Mariupol were held, including members of the Azov Regiment, the 36th Marine Brigade, border guards, and National Police officers. In addition, Ukrainian civilians, including volunteers and evacuees, were detained and held in horrific conditions despite their protected status under international law.

The colony’s proximity to the front line (approximately 14 km as of July 2022) placed detainees at constant risk, a direct violation of international humanitarian law, which requires POWs to be held in safe locations away from active hostilities.

Mass execution in Olenivka in the early hours of 29 July 2022, stands out as one of the gravest war crimes against POWs when at least 53 Ukrainian POWs were murdered, with another nearly 139 injured. Those killed or wounded were members of the Azov Brigade who had surrendered from the Azovstal steel plant.

Two days before the incident, 193 Azov servicemen were moved into the industrial barrack. On the evening of 28 July, the POWs were locked inside the barracks, and just a few hours later, explosions occurred. Following the explosions, prison guards and leadership refused to help the wounded. Instead, they were seen standing and sipping coffee at the site of the massacre or firing into the air to prevent survivors from approaching the gates. Immediately after the explosion, colony staff freely moved around the colony without fear of subsequent shelling, despite later claims by Russia that the explosion was due to Ukrainian shelling. Despite the arrival of ambulances, the colony staff deliberately refused to provide medical aid to the injured POWs.

Following the mass killing, surviving POWs, including many severely injured, were forced to clean up the site, remove corpses and debris, and sort through body parts in the ruined barrack, according to OHCHR findings.

The ICRC was unable to gain access to the Olenivka Colony after the mass killing. Furthermore, the UN’s response to the Olenivka war crime was weak. Although Secretary-General Guterres launched a Fact-Finding Mission in August 2022, it never visited Ukraine and was disbanded in January 2023. Ukrainian Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets criticised the mission’s composition, which included biased individuals, such as Brazilian General Carlos dos Santos Cruz, a former military attaché in Moscow and Minister-Secretary in the government of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. A few days before the war began, on February 16, 2022, Bolsonaro met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, where he expressed “solidarity” with Russia.

Another member of the Mission was Ingibjörg Gísladóttir, who had been repeatedly criticised for ignoring Russian human rights violations while at the OSCE. The decision to shut down the Mission without results underscored the UN’s inability to act effectively in the face of Russian aggression.

In December 2024, Human rights organisations filed a submission with the International Criminal Court calling for an investigation into the mass murder and torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war in Olenivka.

According to numerous testimonies from former detainees and reports by international organisations, systematic torture, physical violence, and horrific treatment were widespread at Penal Colony No. 120 in Olenivka. These practices were a routine part of the facility’s function under Russian control.

Detainees were frequently blindfolded with duct tape, their hands bound, and hoods placed over their heads during transport or movement. Any perceived disobedience, including sitting or lowering one’s hands incorrectly, could result in beatings with rubber batons. Detainees, including both civilians and former soldiers, were tortured with electric shocks. Electrodes were attached to their toes or their bodies were sprayed with water before being shocked while lying on metal tables.

The so-called “disciplinary isolation block” (DIZO) was one of the most brutal episodes described. There, women and men were held in overcrowded, unsanitary cells with no access to functioning toilets, often forced to defecate where they slept.

The colony’s overcrowding itself became a method of torment. According to testimonies, up to 20 people were put in cells designed for 4 and 55 POWs were put in cells designed for 8. Prisoners had to sleep in shifts on concrete floors, deprived of bedding and fresh air. Screams of beaten POWs were heard every night from nearby cells.

Medical care in Olenivka Penal Colony No. 120 was nonexistent and deliberately denied. Multiple testimonies from former detainees describe medical neglect, lack of access to essential care, and cruel disregard for suffering.

Wounded Azovstal defenders received only minimal painkillers upon arrival. Many were left without proper treatment for severe injuries, including shrapnel wounds, broken limbs, and internal bleeding. There were no medications, no doctors, and no boiling water available for the sick.

After the Olenivka war crime in July 2022, dozens of severely injured POWs had to wait for hours before being evacuated, but not by ambulance, but in KAMAZ trucks. With gunshot wounds, burns, and internal trauma, they were thrown into the metal beds of trucks, forced to crouch or lean on their hands to avoid the searing pain from sitting on the hard floor. Some of the wounded never made it to surgery in time. Medical assistance was often provided only because the explosion had caused public visibility, briefly interrupting the usual neglect.

The OHCHR noted that following the mass killing, injured POWs were given no professional medical aid inside the colony. Instead, other detainees cared for them, using rags and bare hands. Some of the wounded bled out, waiting for help.

Starvation, thirst, exposure to human waste, and denial of hygiene were widespread tools of repression. Basic survival needs were used as levers of coercion and submission. Daily food rations were meagre and given in dirty dishes. Clean drinking water was a luxury. Detainees received no more than 150–200 ml of drinking water per day, and even that was not guaranteed. Technical water, used for washing and sanitation, was also rationed and often unavailable for several days at a time. Guards explicitly told POWs: “Be grateful we feed you at all”.

Toilets in the disciplinary isolation unit were non-functional. Waste accumulated in clogged drainage pits, releasing stench and serving as a source of disease. For the first weeks, the use of the toilet was forbidden, which was another method of deliberate humiliation and torture. Prisoners had to relieve themselves in buckets or not at all.

Women in detention were denied basic hygiene products, including menstrual pads, for months. Without access to any sanitary materials, women were forced to bleed in clothing and sleep on blood-stained concrete floors. There were women of all kinds – pregnant, mothers of small children, National Guard accountants, and completely civilian women.

Captivity in Olenivka Penal Colony No. 120 was built around a system of total control, fear, and mental exhaustion. Prisoners were subjected to conditions designed not only to break their bodies, but also to crush their will and identity.

Detainees were deprived of any connection to the outside world and held in total informational isolation. Instead, they were exposed only to Russian propaganda and false reports. POWs were told that Kharkiv was already occupied and Russian forces were already near Kyiv.

Sensory deprivation and constant uncertainty were key methods of pressure. Prisoners were regularly blindfolded, had their hands and eyes taped, or were forced to keep their heads down for hours at a time during transfers and interrogations. Lights in cells were left on around the clock, or, conversely, cells were kept in total darkness. Loud noises, shelling, shouting, or the cries of tortured detainees were a constant background sound.

Detainees were told they would be held in the colony “for 10 years or more,” or, as prison chief Serhiy Yevsyukov often put it, that their families would be told they had “flown into space”.

Interrogators and guards often played psychological games, threatening collective punishment or promising exchanges that never came. At times, guards forced prisoners to step over a Ukrainian flag, and those who refused were punished.

A truck stopped near the barracks, releasing two or three people at a time. About ten soldiers in balaclavas stood nearby with dogs and batons. They began beating our boys. We watched from the windows of our buses. Then they were ordered to run. As they did, the dogs were unleashed and bit at their legs. When the boys fell, they were beaten again with batons. It happened to every one of them” – Anastasiia Rustamova, 36th Separate Naval Infantry Brigade, on the “reception” at Olenivka Colony.

“His call sign was ‘Casper.’ A quiet, calm guy. He was ‘300’ [wounded] — he’d survived two airstrikes in Mariupol and suffered facial burns. During the ‘reception,’ he was beaten to death… He stood right in front of me. If he hadn’t died, they would have beaten us, those of us standing behind him, with the same force… There was a guy on a crutch. They took his crutch and beat him with it. I saw him lying while the prison guards stood over him, just watching to see what would happen next” – а combat medic on the “reception” at Olenivka Colony.

“A half-destroyed building with shit dripping down the walls, perpetually clogged sewage, and freezing cold. It was always cold, all the time. Mostly because of the concrete floor. No benches, no beds, nothing to lie on properly. The toilet was right inside the cell, always blocked and unusable. The walls were covered in mould and fungus. Cold and concrete… We constantly heard the beating of prisoners of war. At the same time, they played music to drown out the screams of pain” – Kostiantyn Velychko, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“An Azov fighter was beaten upon arrival — so badly he couldn’t rise from his knees. One of the guards shouted, ‘Look, they brought fresh meat!’ Then they forced him to clean the toilet with his bare hands” – а prisoner of war on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The guys told us they had been physically abused. The Russians attached electrodes to their toes or placed them on a metal table, sprayed them with water, and turned on the power” – Kostiantyn Velychko, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The sewage system was set up in such a way that everything simply accumulated in a drainage pit, which was always clogged. During the first weeks, it was especially unbearable — they didn’t allow us to use the toilet. That was a specific form of torture. We were surrounded by filth, decay, and freezing cold” – Hanna Vorosheva, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“Drinking water was something we especially lacked. We could expect just 150–200 ml per person per day. Sometimes, we didn’t even get that” – Hanna Vorosheva, a volunteer from Mariupol, on detention conditions in Olenivka.

“The administration representatives calmly watched people die through the night. All they were missing was popcorn. Through the fence, they watched me perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. They didn’t arrange any evacuation. During that time, five more people died — people we couldn’t help… Everyone was transported in ordinary trucks” – а combat medic on the explosion in the barracks.

“In addition to shrapnel, our bodies were full of mineral wool fibres. For a month afterwards, we kept pulling those needles out. It burned. Can you imagine mineral wool burning? Your whole body itches and burns. And we were barefoot — our feet shredded from walking over broken glass and debris. Many of our guys suffered severe burns” – Azov serviceman, call sign “Lemko,” on the explosion in the barracks.

“I know there were ambulances behind the gates. We heard them. They arrived 30 minutes after the explosion. We even passed them one of our wounded, call sign ‘Karas.’ We passed him under the fence in a sleeping bag. After some time, they returned him. He was still alive. They said he had no chance. We asked, ‘Should we hand over someone else?’ They said no. Then we asked for a needle so we could perform a decompression on those with chest wounds. They refused” – Azov servicemen on the explosion in the barracks.

“Nothing can prepare you for what we saw there. The entire walkway was covered in blood. People were just crawling — something I could never have imagined. Some had traumatic amputations, deep abdominal wounds, head injuries, or multiple shrapnel wounds” – а combat medic on the explosion in the barracks.

News

see more

“The captives were forced to walk with their heads down”: how the rehabilitation of released Ukrainian soldiers takes place

Ukrainian servicemen released from Russian captivity often arrive at the National Guard’s medical centre in extremely poor condition, both physically and psychologically.

Russia has established a network of torture chambers for Ukrainian prisoners of war.

At least five secret prisons in Russia are holding Ukrainian POWs.

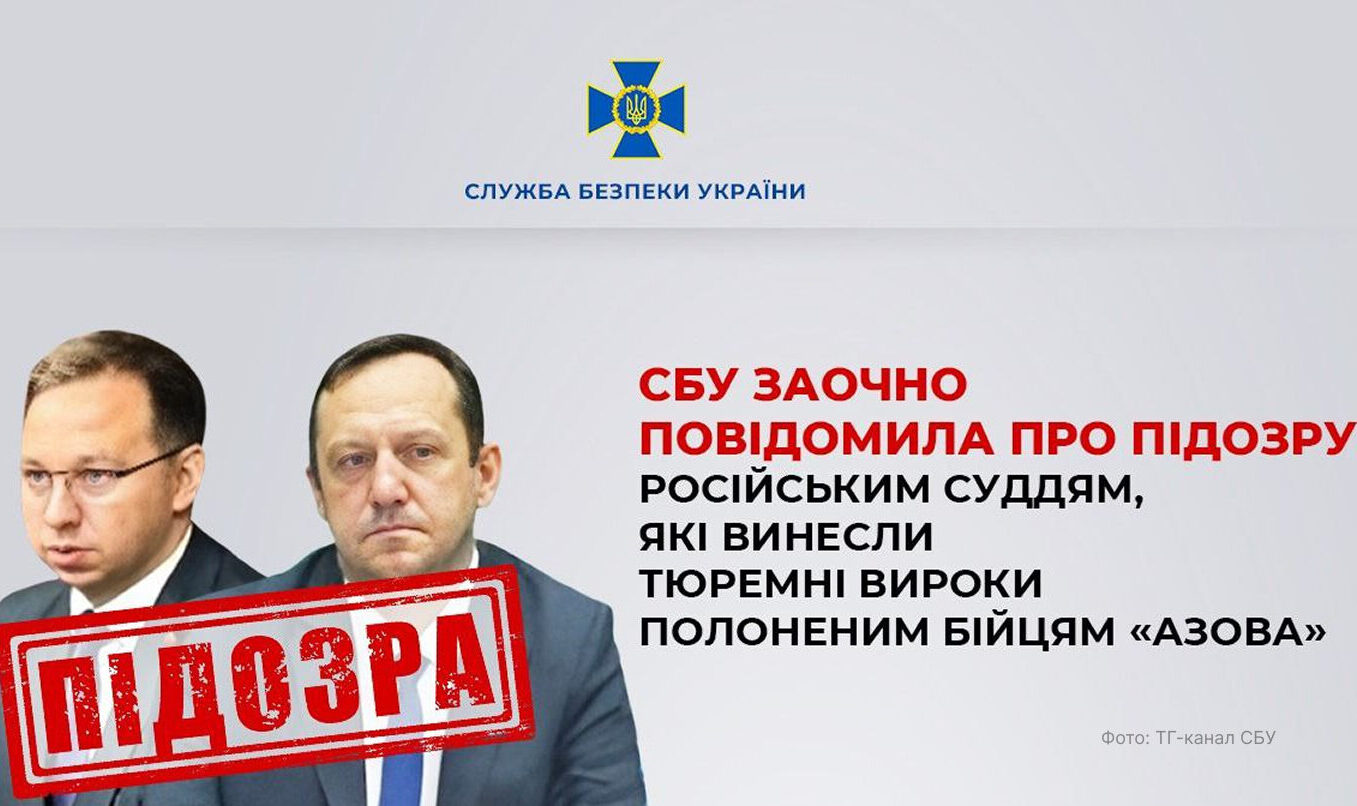

SBU presses charges against russian judges for the unlawful sentencing of Azov Brigade POWs

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) has charged in absentia two judges of Russia’s Southern District Military Court, Konstantin Prostov and Sergey Obraztsov, with war crimes against Ukrainian prisoners of war.

questions & answers

You can make a difference

Have a question, a message, or something important to share?

Whether it’s information, a concern, or a word of support, we want to hear from you.

Every voice matters.